Intro

Pleasure gardens were the great melting pots of eighteenth-century society. London pleasure gardens in particular were phenomenally successful. First opened in 1746, Ranelagh pleasure gardens in Chelsea boasted acres of formal gardens with long sweeping avenues, down which pedestrians strolled together on balmy summer evenings. Other visitors came to admire the Chinese Pavilion or watch the fountain of mirrors and attend musical concerts held in the great 200-foot wide Rotunda. Novelist Tobias Smollett described how the nightly illuminations and magic lanterns at Ranelagh ‘made me almost think I was in some enchanted castle or fairy palace’. Originally designed to appeal to wealthier tastes, pleasure gardens soon became the haunt of the rich and poor alike, where both aristocrats and tradesmen enjoyed the rural retreat side by side.

The 18th century saw the emergence of the ‘Industrial Revolution’; the great age of steam, steel and mechanised manufacturing that changed the face of the Western world forever. New weaving processes in the late 1700s allowed for the mass production of the cheap and light cloth that was highly sought after in Britain and her colonies.

New factories employed hundreds of people, including many small children, whose nimble hands made light-work of spinning. Many factories were dismal and highly dangerous, often likened to prisons, where workers encountered harsh discipline enforced by factory owners. Numerous children were sent there from workhouses or orphanages to work long hours in hot, dusty conditions, and were forced to crawl through narrow spaces between fast-moving machinery. A working day of twelve hours was not uncommon, and accidents happened frequently.

Wealthy readers could browse the guide to find details of each lady’s personality, physical appearance and background. The appearance of prostitutes at evening time was a familiar part of life in eighteenth-century towns, and prostitutes catered to all tastes among the rich and poor alike. In London, scores of street walkers plied their trade up and down the Strand, and swarmed in the theatres and taverns of the capital. Dozens of infamous bawdy-houses could be found up narrow alleyways and down side streets, and even ships moored on the Thames were sometimes converted into brothels.

Captain James Cook (1728–1779) had a mission to boldly go where no white man had gone before – pioneering voyages to explore and survey Newfoundland, Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific. He was a brave, practical and thorough Yorkshireman, always concerned with his crew’s welfare. This is a description in his journal of an encounter with cannibals from 1775, near the end of his second voyage of discovery on the ships Resolution and Adventurer. Putting indignation aside for the sake of scientific observation, Cook tests rumours of cannibalism. He cooks a piece of flesh from a corpse found on the beach, to find that ‘one of the Canibals [sic] eat it with surprising avidity’.

Original text:

[some of the officers went on shore to amuse themselves among the Natives where they saw the head and bowels of a youth] who had lately been kill'd, lying on the beach, and the heart was stuck on a forked stick which was fixed to the head of one of the largest Canoes. One of the gentlemen bought the head on board with them where a piece of the flesh was broiled and eat by one of the Natives before all the officers and [most?] of the crew. I was on shore at this time but soon after returned on board and was informed of the above circumstances, and found the quarter deck crowded with the Natives and the mangled head, or rather part of it for the under jaw and lips were wanting, lying on the [?]. The scul had been broke on the left side just above the temples, the remains of the face had all the appearence of a youth under Twenty.

The sight of the head and the relating the above circumstances struck me with horror and filled my mind with indignation against these Canibals; curiosity however got the better of my indignation, especially when I considered it would avail but little, and being desireous of becoming an eye wittness to a fact which many had their doubts about, I ordered a piece of the flesh to be broiled and brought on the quarter deck, where one of these Canibals eat it with a surprising avidity. This had such effect on some of our people as to make them [warn?] who came onboard with me.

[Bediddie/Bediddu?] was so affected with the sight as to become perfectly motionless and seemed as if metamorphosed into the [Statue?] of horror: it is, utterly impossible for Art to depict that passion with half the force that it appeared in his Countinance. When roused from this state by some of us, he burst into tears, continued to [?] and scold by turns; told them they were Vile men and that he neither was, nor would be no longer their friend. He even would not suffer them to touch him, he [?] the same language to one of the gentlemen who cut off the flesh, and refused to accept or even to touch the knife with which it was done. Such was this islanders indignation against this vile Custom and worthy of imitation by every rational being—

The eighteenth century was the age of ‘commercialised leisure’, according to the historian Sir John Plumb. Thanks to the growth of an urban middle class, rising incomes, and new ideas about how people should socialise and converse with one another, it was a period in which paid-for entertainment proliferated, especially in large, cosmopolitan cities like London.

One of the most significant innovations in eighteenth-century leisure was the pleasure garden; a dedicated outdoor space for entertainment, for which a ticket was needed to gain entry. In London, the gardens at Vauxhall, near Lambeth, and at Ranelagh, in Chelsea, were the largest and most spectacular of their type; while other, smaller gardens were established at Sadler’s Wells, Marylebone and Hampstead – all of these sites were on the rural outskirts of London.

They were sites for music, dancing, eating and drinking – and regular fireworks, operas, masquerades and illuminations. Laid out as formal gardens, with shrubberies and miniature waterways, and dedicated buildings for performances and for eating, they were places to see the latest in art and architecture. Ranelagh boasted a pavilion in the fashionable Chinese style, while Vauxhall displayed paintings by William Hogarth and Francis Hayman in its supper booths, effectively becoming the first public art gallery in Britain.

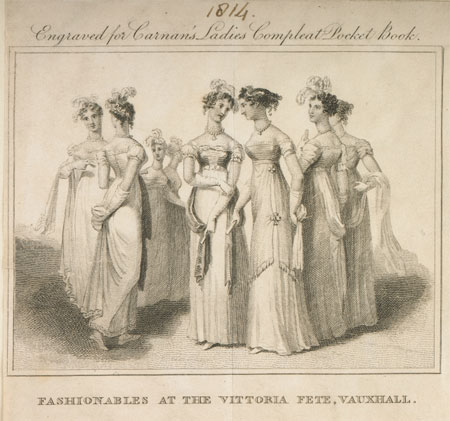

Vauxhall was also the place to go to hear the work of George Frideric Handel, who became a kind of composer-in-residence during the 1730s and 1740s. Aimed at the wealthy, the aristocratic, and the more prosperous sort of merchant and professional families, London’s pleasure gardens were the very best places to see and be seen by the world, arrayed in your most fashionable finery.

The first and most important of these gardens, Vauxhall, was established in 1729 by the entrepreneur Jonathan Tyers. While the site had been a place for Londoners to gather and buy refreshments since the 1660s, Tyers realised that there was a market for paid entertainment. He also knew that charging an admission fee (of one shilling) would discourage pickpockets and prostitutes.

The admission fee theoretically guaranteed that patrons would not have to rub shoulders with the lower classes of the city, for a shilling was a substantial sum of money to an apprentice or servant earning just a few pounds a year. Ranelagh was even more expensive – and exclusive – at two shillings and sixpence; and was considered the most respectable option of all.

Despite these efforts to keep ‘the riff-raff’ of the city outside its elegant gates, Vauxhall had a slightly louche, dubious reputation. Its wooded groves and shady alleyways were the perfect place for a discreet assignation, and the well-dressed prostitute was associated with the garden to the extent that London printshops sold images with titles like The Vauxhall Demi-Rep’, showing beguiling ladies in expensive but revealing clothing.

One of the most scandalous events at Vauxhall occurred at a fancy dress masquerade in 1749, when the courtier Elizabeth Chudleigh arrived 'dressed' as the classical figure Iphigenia – her costume consisting of nothing more than a thin scarf draped over her body, showing off more than it hid. Again, the press and printsellers had a field day. Even respectable Ranelagh had its disturbances, such as the 1764 riot caused by servants and coachmen angry at the abolition of ‘vails’, or tips.

So vivid was the idea of the London pleasure garden as a place of danger, debauchery and drunkenness that it was frequently used as a backdrop for contemporary novels, ballads and prints. The heroes and heroines of numerous 18th and early 19th century novels end up in a pleasure garden at some point, and usually worse off at the end of the evening than at the beginning of it – from Frances Burney’s virtuous Evelina, pursued through the trees of Vauxhall by men intent on harassment and maybe worse, to William Thackeray’s comic character Jos Sedley, in Vanity Fair, suffering literature’s worst hangover after a night of Vauxhall punch.

There was nothing quite like the London pleasure garden, and no modern equivalent exists. It was a place where the glittering world of wealth, fashion and high culture showed off its seedy underside; where princes partied with prostitutes, and the middle classes went to be shocked and titillated by the excess on display. Simultaneously an art gallery, a restaurant, a brothel, a concert hall and a park, the pleasure garden was the place where Londoners confronted their very best, and very worst, selves. When Vauxhall finally closed in 1859, it was the end of an era, never to be repeated.

No comments:

Post a Comment